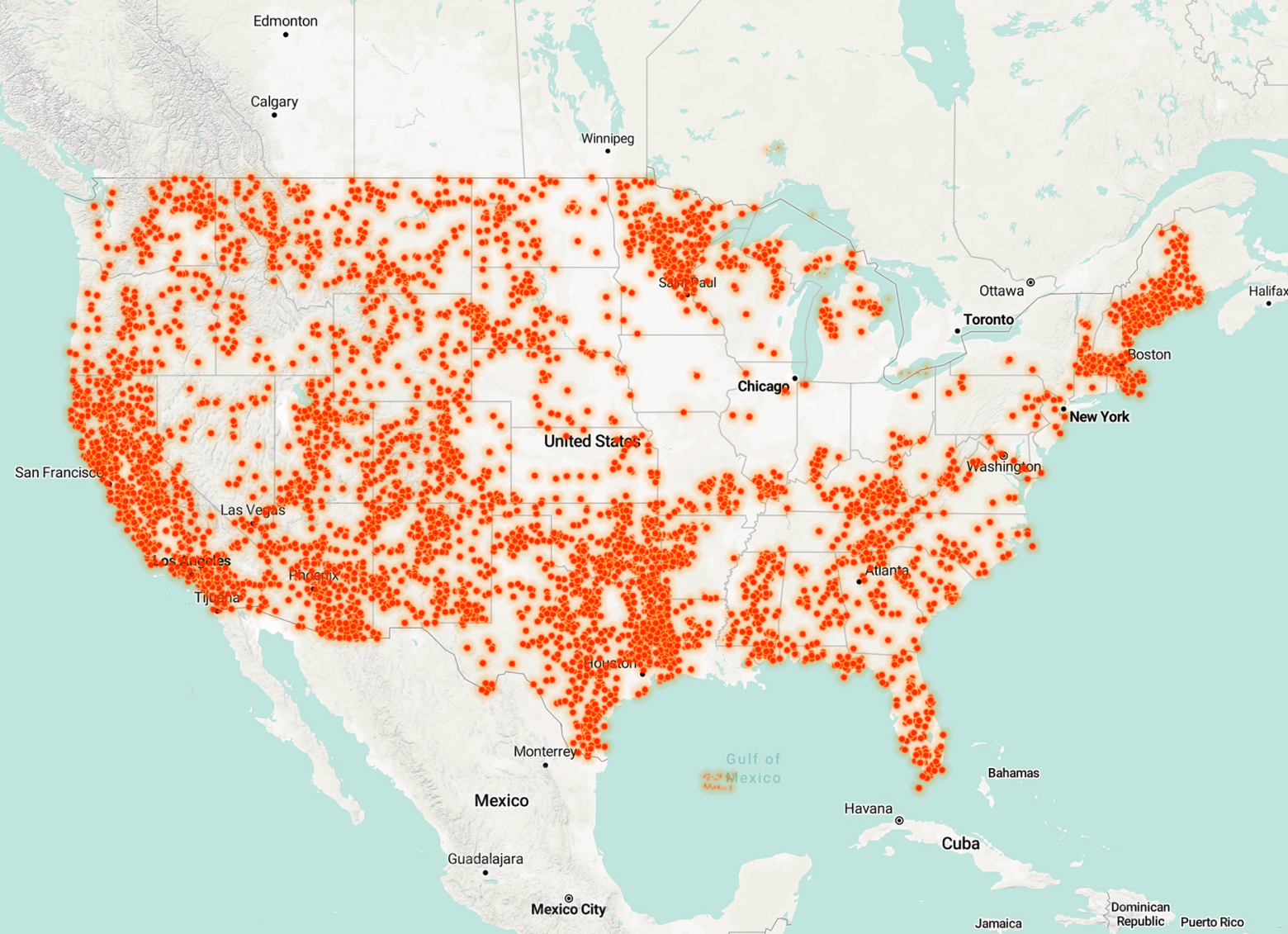

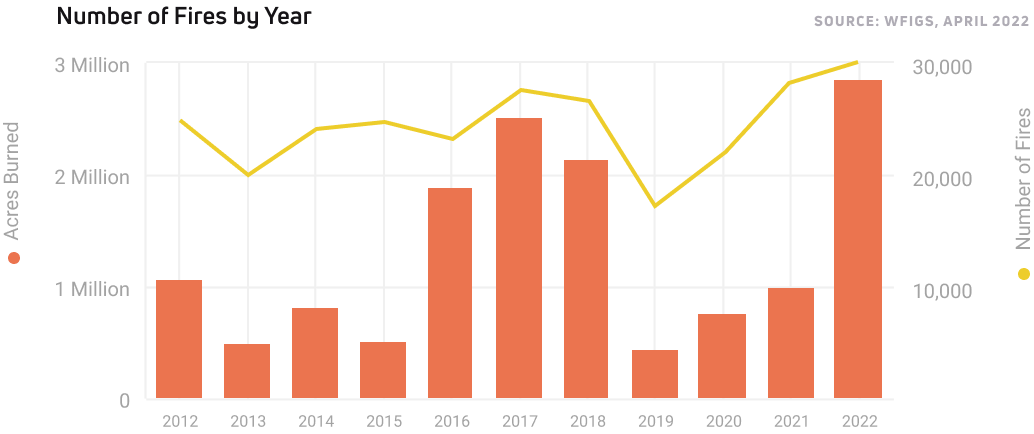

Prepared June 24, 2022 Wildfires are not just a New Mexican or Floridian problem, they’re a national problem that needs more attention. The above may look like some vision of where electric car chargers would be built, but it’s instead every location of a wildfire that has happened since the beginning of 2022. Year to date, 2022 has seen more fires than any other year in the past 10 years. The 29,966 individual fires this year is 29.3% above the 10 year average of 23,212. While hurricanes, floods, and rising temperatures get the most media and political attention, the science and tech driving our nation’s preparation, mitigation, and response to one of the largest drivers of and consequences from climate change – wildfires – remain outdated in the face of the rapid escalation we are seeing in terms of wildfire frequency, scale, and fire behavior. Wildfires are at the center of a perpetual and vicious feedback loop as they both contribute to the factors causing climate change and are fueled by climate change itself. Wildfires produced a record 1.8B tons of carbon in 2021, with 91M tons of carbon dioxide emitted in California alone, 30M tons more emissions than the state emits annually from power production. It is often said that what the United States and citizens around the world are witnessing in terms of changes in our climate and the seemingly unrelenting devastation from natural disasters is the “new normal”. This is not the new normal. We are decades if not generations away from seeing a steady state when it comes to the impacts of climate change. The impacts of escalating climate change, accelerating population growth and development in wilderness-adjacent landscapes known as the Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI), the unrelenting buildup of fuels in fire-prone ecosystems, and persistent resource constraints across the wildland firefighting system have resulted in fire behavior that upends predictive models and fire management tactics year after year. Today’s wildland firefighters are lacking the real-time data and technological strategic support that their peer first-responders in other disasters have at the click of a button. Most wildfire incident managers still rely on tools and resources that have gone unchanged for decades. California, for example, has not updated its state-wide fire risk maps since 2007. A ubiquitous need among federal and state fire agencies, along with their private sector partners and stakeholders, is strategic, timely, and actionable data. Generations of wildland firefighters and leaders have relied on hard-earned experience and first, or second-hand knowledge to provide the foundation of their strategic and tactical approach. Novel technology and data sets not previously available have the power to augment that experience to support a safer and more effective response. For example, when responding to a new wildfire start, incident managers often rely on past experience fighting fires in the same region, or fires on landscapes with a similar geographic and fuel profile, to inform their initial attack and potentially extended attack strategy. With modern tools and strategic data resources, we can develop scientifically-derived models that identify areas with the highest likelihood of successfully controlling a fire (known as Potential Control Locations or PCLs) or geographic areas that are most likely to enhance suppression efforts (known as Suppression Difficulty Indices or SDI). Even before fire season, planners can use these risk data analytics to enhance the effectiveness of their prevention and mitigation programs. These programs work to reduce the risk to life, property, and the environment but also to enhance the effectiveness of active incident response. For example, by utilizing PCLs and SDIs mentioned above, wildfire planners would be able to more accurately identify areas of high risk to firefighters and the public and target those areas for fuels treatment projects. These data-driven risk products can also support the strategic placement of fire resources to areas of highest risk where suppression may be most difficult and labor-intensive. By using risk data in both strategic and operational planning, feedback loops can become smarter and empirical lessons learned can be applied from one fire to another in service of reducing risk to first responders and communities alike. What we need to both combat the escalating impacts of climate change and be prepared for what eventually will be the “new normal”, is a true public-private partnership to develop the modern tools that federal, state, and local governments need. The recently passed Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocates $4.5B for federal wildland fire management efforts over the next five years. Fire-prone states across the country have seen increases in their own wildfire budgets. This combined historic investment focuses not only on response and suppression but also the full spectrum of wildfire management from mitigation and preparedness through to recovery. The Department of the Interior alone is allocating $72M to improve its use of technology and equipment to detect and respond to wildfires with another $10M allocated to fund high-priority fire science research. The speed at which both federal and state agencies can deploy these funds will make all the difference in how the most fire-prone areas of the country fare over the upcoming fire seasons. The more we bridge the gap between science and action, the more we can work to mitigate the impact of wildfire on our communities.

The data: bigger fires that burn more land.

Private sector innovation cannot advance without a deep partnership with government experts and access to greater information sharing. Our company, Cornea, has benefited from a long-standing relationship with the United States Department of Agriculture including a recent grant award through their Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program through which we have been given the resources to further develop our machine learning platform.